ARTS INDEPENDENT

Jim Catapano reviews

The Meeting: The Interpreter

An Historic Moment Captured Through a Surreal Lens

Catherine Gropper Crafts a Gripping and Innovative Look at Events Leading up to the 2016 Election

The Meeting: The Interpreter is a Tour De Force of modern theater—what at first seems like a traditional two-hander becomes something far more unique and spectacular. It is centered around a notorious meeting at Trump Tower in 2016 that may have been the smoking gun in alleged collusion between the Trump Campaign and Russia, and the Congressional Hearings that followed. A large screen completely covers the stage as actors Frank Wood (Tony winner, Side Man) and Kelly Curran (HBO’s “The Gilded Age”) take their places; they appear first as images, with the backdrop of a Senate hearing room to introduce themselves and the setting in a blisteringly fast round of dialogue. The screen projection then slowly moves to the audience’s right, revealing the actors and stage crew behind it. Two crew members operate the camera on a railroad track that winds around the stage, zooming in on the actor’s faces, hands, and unexplored aspects of the set that all play a part in the unfolding story.

Wood is the International Interpreter of the title, a Russian-born man who sees himself as an American; he is the key witness in the events of the day who just wants to live in peace and quiet. Curran is a journalist, the Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya (believed to have had a dossier on alleged Clinton shenanigans), and many other pivotal players in the world-changing event. (Note: a quick review of the actual historical events prior to attending will greatly enrich any theatre-goers experience of the production. And be sure to study up on the Magnitsky Act of 2012.)

The set by Jim Findlay is like a third character in the production; it is full of surprises that the tracking camera slowly reveals—a sound booth in the back, an open locker filled with paraphernalia around a hidden corner. Puppets by Julian Crouch depict the players involved in the Trump Tower meeting (including the infamous Paul Manafort); their large, somewhat grotesque heads plopped on tiny naked bodies. There is interpretive dance (choreography by Orlando Pabotoy); many bizarre turns, such as Curran nailing her many neckties to a block of wood; there are even snippets of singing. It all paints a vivid and unforgettable look of a fateful moment in time that haunts our country and the world to this very day.

Wood and Curran are astonishingly good in what is a very challenging production —switching characters, accents, and even wigs at a feverish pace—and using every device in the theatrical playbook to command the stage and tell the tale. Added power is provided by the lighting by Barbara Samuels and sound by Daniel Baker and Co., and it is all held together by the brilliant.

The staging is striking; at the beginning, a large screen shows close ups of a journalist interviewing the Interpreter before moving to the side and revealing the full picture. Filmed close-ups of the actors throughout the play, add effects, changing the moods, all shown on the large screen, a creative choice by Mertes flawlessly executed. – Stage and Cinema, Paola Bellu

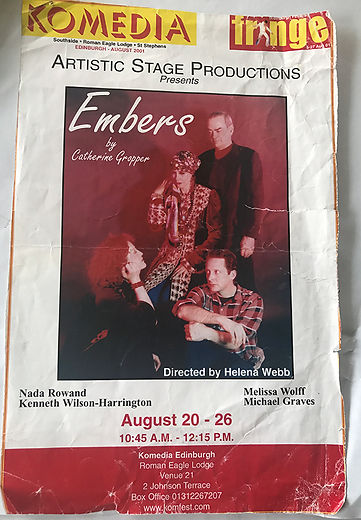

**** Embers

**** Embers

Published: 01:00 Saturday 25 August 2001

Actress Nada Rowand makes her Edinburgh debut in this portrait of a New York artist. With kohl-rimmed eyes and fake lashes her appearance is more dame than sculptress. Wearing a helmet, its Perspex screen pulled over her face, she looks like a diva working on a construction site. Rowand gives a striking performance as the late Louise Nevelson, lauded at the time as one of the greatest female sculptors of the 1980s. "I was born to create," she declaims. "I am all the female artists before and after." But Nevelson’s glamour is tainted by cynical, tragic undertones. Her grown son - a suitably sultry performance from Kenneth Wilson-Harrington - is a walking reminder of the sacrifices made for her art. He nurses his feelings of neglect with the care Nevelson reserves for her sculptures. The broken mother/son relationship is played out in the shadows. On the rare occasions preppy Nick turns up at his bohemian mother’s studio, he appears in the doorway and speaks in a monotone, his duffle coat buttoned to the neck, while Nevelson, with a deep, throaty voice, lolls around with her bottle of vodka. Writer Catherine Gropper deftly pulls together the various strands - love story, family crisis, the rise of an artist - to create a vibrant story. Covering the whole period from the 1960s to the 1980s is a lot to pack into a 75-minute show , but Gropper writes with conviction, bringing Nevelson to life with the care and attention of a craftsman.

Theater| THEATER REVIEW

THEATER REVIEW; Louise Nevelson, Sacred Monster, Takes a Bow

By ANITA GATES FEB. 1, 2002

I love hearing about brilliantly talented people who seem to be despicable human beings. So naturally I'm interested in Louise Nevelson.

So is the theater world this season. Anne Bancroft will play Nevelson in Edward Albee's new work, ''The Occupant,'' opening next month at the Signature Theater. Twenty-some blocks away, at the Chelsea Playhouse, Catherine Gropper's Nevelson play, ''Embers,'' opened on Wednesday night.

And the woman it portrays is entirely too nice. Nevelson's life is an easy subject to make interesting. She was born in Kiev in 1899 and was so traumatized by her father's leaving for the United States that she stopped talking for six months. The whole family soon settled in Maine, where she developed a unique values system. ''If a so-called lie will be a tool for me to fulfill myself,'' she once said, ''I'll use it and have no morals about it.''

She married a steamship owner, Charles Nevelson, in 1920; had a son, Myron; and abandoned them both, telling her son more than once that she wished he had never been born. (Myron Nevelson, known as Mike, and Stephen Sondheim could probably find something to talk about.) In New York she drank, picked up men in unlikely places and pretty much did what she pleased. Beginning in the 1940's, with her first gallery show, she built a worldwide reputation as a dazzlingly original sculptor and painter. (Her 1958 sculpture ''Sky Gate,'' at the World Trade Center, was destroyed on Sept. 11.) After Nevelson died, in 1988, her longtime assistant and her son began battling over possession of some of her art.

The origins of that battle seem to be the focus of ''Embers,'' a four-character play with most of the names changed. It begins the day that Dede (Melissa Wolff) takes the job as assistant to Nevelson (Nada Rowand). Soon the artist's son, Nick (Kenneth Wilson-Harrington), drops by Nevelson's place to exchange insults about art, one-night stands and the states of both their livers. Meanwhile, as Nevelson is scavenging for useful objects in a museum's garbage one night, she meets and takes home a security guard, Will (Michael Graves), whom Ms. Gropper intends as a composite figure representing various men in Nevelson's life.

The structure of the play, which is intermissionless, works well, with scenes set from 1950 to 1985, mostly in Nevelson's studio. The cast, forcefully directed by Helena Webb, does a good job of defining the characters, even when, near the end, Ms. Gropper's language lapses into the highly unlikely. ''May's lilacs still permeated the night air,'' Nick says, inexplicably, shortly after his dying mother has asked him how she looks. A little later, when she seems to be trying to tell him that her love for him is expressed in her work, she announces, ''You call me mother, but I can only call myself artist.'' For all I know, Nevelson may really have talked that way, but the onstage character can't pull it off.

The flaw in ''Embers'' is its inability to convey a sense of specialness in Nevelson. Here she seems reduced to the emotions and reactions of any parent who feels guilty about staying at the office too late. What is missing is the strange egotistical mindset that convinces some famous people that they, and only they, matter in the universe.

The play is to be admired for putting as much emphasis as it does on Nevelson's work. Ms. Gropper treats her subject more than fairly and gives hints of what motivated her. Terry Leong's costumes are appropriately Nevelsonian, with lots of scarves and layers and the inevitable turban.

''Embers,'' which had a one-week workshop production last year at St. Peter's Church and was presented at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, continues at the Chelsea Playhouse through Feb. 24.

EMBERS

By Catherine Gropper; directed by Helena Webb; general management,, HelCat; sets and sound by Jared Coseglia; set sculptures by Cory Grant, Paul Hudson, Magin Schantz and Mr. Coseglia; individual sculptures, Katerina Fiore; lighting by Graham Kindred; costumes by Terry Leong; production stage manager, Megan Smith; assistant stage manager, Marissa Daniella Duricko. Presented by Artistic Stage Productions and the Stearn Company. At the Chelsea Playhouse, 125 West 22nd Street.

WITH: Nada Rowand (Louise Nevelson), Melissa Wolff (Dede), Michael Graves (Will) and Kenneth Wilson-Harrington (Nick).

Miss Crandall’s Classes

July 10, 2009 by Marcia Kirtland

Miss Crandall’s Classes is the heartfelt drama of one woman’s strong belief that everyone has the right to an education. The teacher’s willingness to put her own life and reputation in jeopardy, to help others discover the joy of learning, seems like a straightforward story; however it is anything but simple.

In 1830’s Connecticut, Prudence Crandall runs a school for girls in a small town. This is a time when blacks are not only considered subhuman; it is illegal to teach them to read. Her decision to accept Sarah, her young free black housemaid, into her school as a pupil brings opposition from her student’s families, and the town authorities, as she knows it will. As her white students withdraw from the school, Prudence fills her classroom with black students eager to learn. She is soon arrested, put on trial for her actions, and ultimately freed. When the town ‘evil doers’ contaminate the well at the school, and burn the classroom, she finds refuge and a match for her ideals in a local minister.

This play, done as a reading, offers an authentic sense of the times and its prejudices. It takes us into the everyday lives of people in the 1830’s, and, sadly, what we see is the result of their fears. Salome Jens’ reading of Prudence gives a strong interpretation of her character’s struggle to understand how others can fail to see, with her clarity, that this is the right path; her passion for and mission to teach everyone never waivers. Latonia Phipps as Sarah is lively and engaged, and we see on her face that her concern and affection for Prudence is as strong as her passion for learning and a free life.

The story is based on the author’s research into actual events of the time. Her tale is compelling, however a full-scale production would help the audience to fully experience all the storyteller had in mind.

Zoe Caldwell directed a staged reading with Andrea Marcovicci at The Drama Bookstore.

by Catherine Gropper

Directed by Jessica Bauman

Produced by Promise Productions LLC

Reviewed by Marcia Kirtland